News & Insights

Stay up-to-date with the latest news about Zuellig Pharma and the healthcare industry in Asia, as our experts from across the region share their insights.

Zuellig Pharma and Karo Healthcare strengthen partnership across key markets in Asia

Zuellig Pharma will be the exclusive commercialisation partner for Karo's over-the-counter (OTC) brand Lamisil, a product for the treatment of fungal infections, across Hong Kong, Malaysia, Philippines, Singapore, South Korea, Taiwan and Vietnam.

18 March 2024

Read more

Zuellig Pharma and Viengthong Pharma Forge Strategic Partnership to Enhance Healthcare Accessibility in Laos

This collaboration signifies a pivotal milestone in advancing healthcare infrastructure in Laos. By leveraging the expertise and resources of both organisations, the partnership aims to address critical healthcare challenges, particularly in underserved regions, and improve the overall quality of healthcare services available to the people of Laos, aligning with the key objectives of the Ministry of Health of Laos PDR.

12 March 2024

Read more

Importance of driving the need for innovative and efficient solutions across the healthcare value chain

With evolving patient needs, emerging disease areas and new innovations driving this fast-moving landscape, we need to collectively prioritise access to healthcare, affordability and sustainability to benefit the health of communities across Asia.

21 February 2024

Read more

Zuellig Pharma acquires Cialis® (Tadalafil) and Alimta® (Pemetrexed) from Lilly in select ASEAN markets

The acquisition of Cialis and Alimta marks a major milestone in the evolution of Zuellig Pharma to becoming an integrated healthcare solutions company. It demonstrates the increasing strength of ZP Therapeutics, which has extensive in-market expertise and capabilities in driving growth of healthcare products in Asia.

05 February 2024

Read more

Zuellig Pharma CEO John Graham appointed a member of 2024 Board of the US-ASEAN Business Council

The US-ASEAN Business Council has spearheaded efforts that highlight regional gaps and opportunities across individual sectors such as biopharma and healthcare.

19 January 2024

Read more

Zuellig Pharma and Substipharm Biologics partner to expand access to IMOJEV® vaccine for Japanese encephalitis across Asia

New commercialisation agreement builds on existing partnership with Zuellig Pharma

16 January 2024

Read more

Zuellig Pharma becomes STADA Philippines’ exclusive distribution partner

Zuellig Pharma, a leading healthcare solutions company, has been appointed as the exclusive distribution partner of STADA Philippines Inc., a fast-growing supplier of high-quality pharmaceuticals and an affiliate of Germany's STADA Arzneimittel AG.

09 January 2024

Read moreAll

Animal Health

Clinical Reach Clients

Consumer Health

Healthcare Providers

Insurance and Corporations

Medical Devices and Diagnostics

Pharmaceutical Companies

Zuellig Pharma and Karo Healthcare strengthen partnership across key markets in Asia

Zuellig Pharma will be the exclusive commercialisation partner for Karo's over-the-counter (OTC) brand Lamisil, a product for the treatment of fungal infections, across Hong Kong, Malaysia, Philippines, Singapore, South Korea, Taiwan and Vietnam.

18 March 2024

Zuellig Pharma and Viengthong Pharma Forge Strategic Partnership to Enhance Healthcare Accessibility in Laos

This collaboration signifies a pivotal milestone in advancing healthcare infrastructure in Laos. By leveraging the expertise and resources of both organisations, the partnership aims to address critical healthcare challenges, particularly in underserved regions, and improve the overall quality of healthcare services available to the people of Laos, aligning with the key objectives of the Ministry of Health of Laos PDR.

12 March 2024

Importance of driving the need for innovative and efficient solutions across the healthcare value chain

With evolving patient needs, emerging disease areas and new innovations driving this fast-moving landscape, we need to collectively prioritise access to healthcare, affordability and sustainability to benefit the health of communities across Asia.

21 February 2024

Zuellig Pharma acquires Cialis® (Tadalafil) and Alimta® (Pemetrexed) from Lilly in select ASEAN markets

The acquisition of Cialis and Alimta marks a major milestone in the evolution of Zuellig Pharma to becoming an integrated healthcare solutions company. It demonstrates the increasing strength of ZP Therapeutics, which has extensive in-market expertise and capabilities in driving growth of healthcare products in Asia.

05 February 2024

Zuellig Pharma CEO John Graham appointed a member of 2024 Board of the US-ASEAN Business Council

The US-ASEAN Business Council has spearheaded efforts that highlight regional gaps and opportunities across individual sectors such as biopharma and healthcare.

19 January 2024

Zuellig Pharma and Substipharm Biologics partner to expand access to IMOJEV® vaccine for Japanese encephalitis across Asia

New commercialisation agreement builds on existing partnership with Zuellig Pharma

16 January 2024

Zuellig Pharma becomes STADA Philippines’ exclusive distribution partner

Zuellig Pharma, a leading healthcare solutions company, has been appointed as the exclusive distribution partner of STADA Philippines Inc., a fast-growing supplier of high-quality pharmaceuticals and an affiliate of Germany's STADA Arzneimittel AG.

09 January 2024

Zuellig Pharma partners with ACEN RES to supply 100% renewable energy to two key distribution facilities in the Philippines

Zuellig Pharma, Asia’s leading healthcare solutions company, has recently signed a new strategic partnership with ACEN Renewable Energy Solutions (ACEN RES), the retail electricity arm of ACEN, to supply 100% renewable energy to power two major distribution facilities in the Philippines – the Santa Rosa Distribution Center and Canlubang Distribution Center.

21 November 2023

Zuellig Pharma CEO John Graham Discusses Healthcare Trends, Sustainability, and Navigating Global Challenges

In a compelling interview with BioPharma APAC, John Graham, the CEO of Zuellig Pharma, delves into the dynamic landscape of healthcare.

09 October 2023

Zuellig Pharma awarded EcoVadis Platinum Medal for third consecutive year and rated leader in carbon management

Zuellig Pharma, a leading healthcare solutions company in Asia, has announced that it has achieved the platinum medal from EcoVadis, the world’s most trusted provider of business sustainability ratings, for the third consecutive year.

13 September 2023

Zuellig Pharma Singapore and GSK Establish Vaccine Distribution Hub to Improve Asia’s Access to Vaccines

Zuellig Pharma, one of the largest healthcare services groups in Asia, today announced that it has entered into an agreement with global biopharma company, GSK, to help set up its first vaccine...

01 August 2023

Interpharma Investments Limited appoints Alfonso “Chito” Zulueta as Non-Executive Chairman

Interpharma Investments Limited, holding company of leading healthcare services provider Zuellig Pharma, today announced the appointment of Mr. Alfonso “Chito” Zulueta as Non-Executive Chairman of its Board. Effective 1 June 2023, Mr. Zulueta succeeds Mr. Patrick Davies, who stepped down after serving as Non-Executive Chairman for four years.

05 May 2023

Zuellig Pharma recognised with a score of “A-” on CDP supplier engagement in industry first

Zuellig Pharma, one of the largest healthcare services groups in Asia, has announced its score of “A-” for Supplier Engagement from global carbon disclosure platform CDP, making it the first and only company worldwide in its activity group to receive this recognition.

27 April 2023

COVID-19 Vaccines Clinical Trial Environment

The World Health Organization officially declared the coronavirus outbreak a pandemic in March 2020. By June 2021, 170 vaccine candidates for COVID-19 had been developed. Of these, 90 were being tested in human clinical trials, 30% had reached Phase 3 and selected vaccines had been authorised for emergency use. There are at least 440 clinical trials with mRNA candidates and at least 140 for viral vectors.

15 December 2022

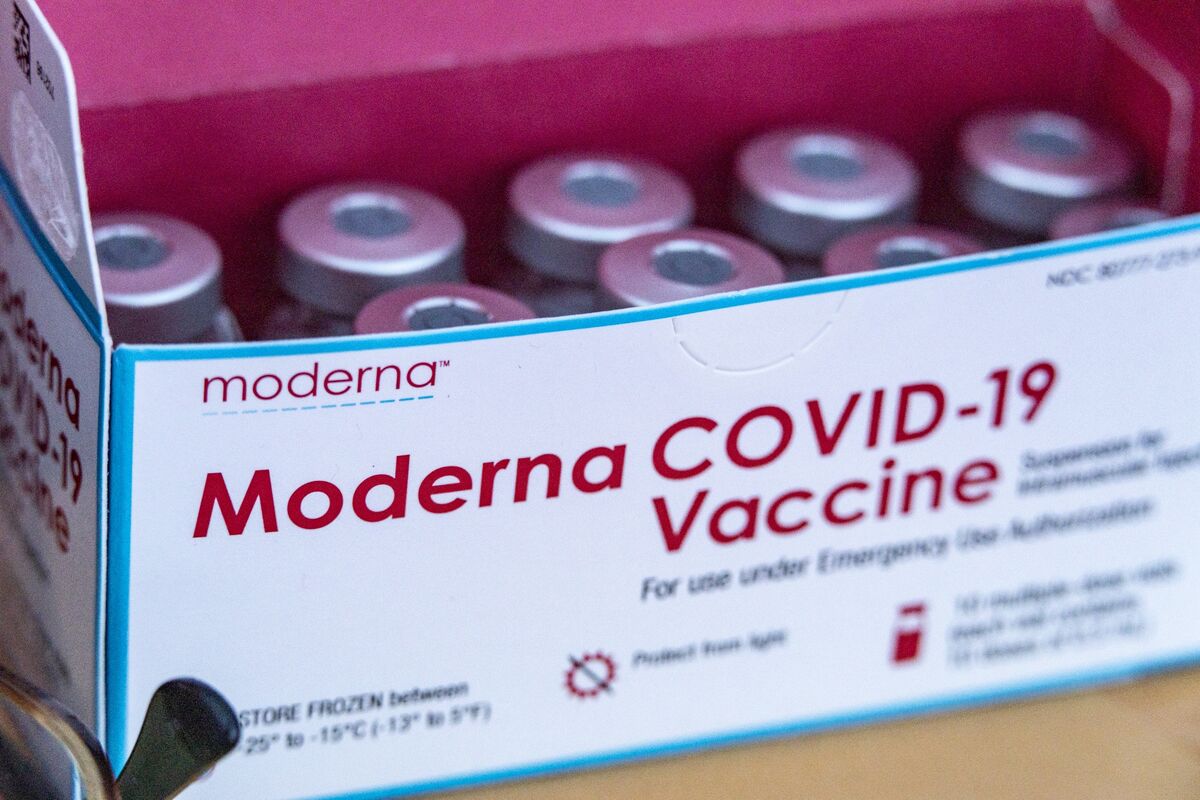

Zuellig Pharma brings logistics expertise to support the Thai government in distribution of one million doses of COVID -19 vaccine Moderna donated by the US government for Thai people

Zuellig Pharma announced its commitment to support the Thai Government, through the Department of Disease Control, Ministry of Public Health.

09 January 2022

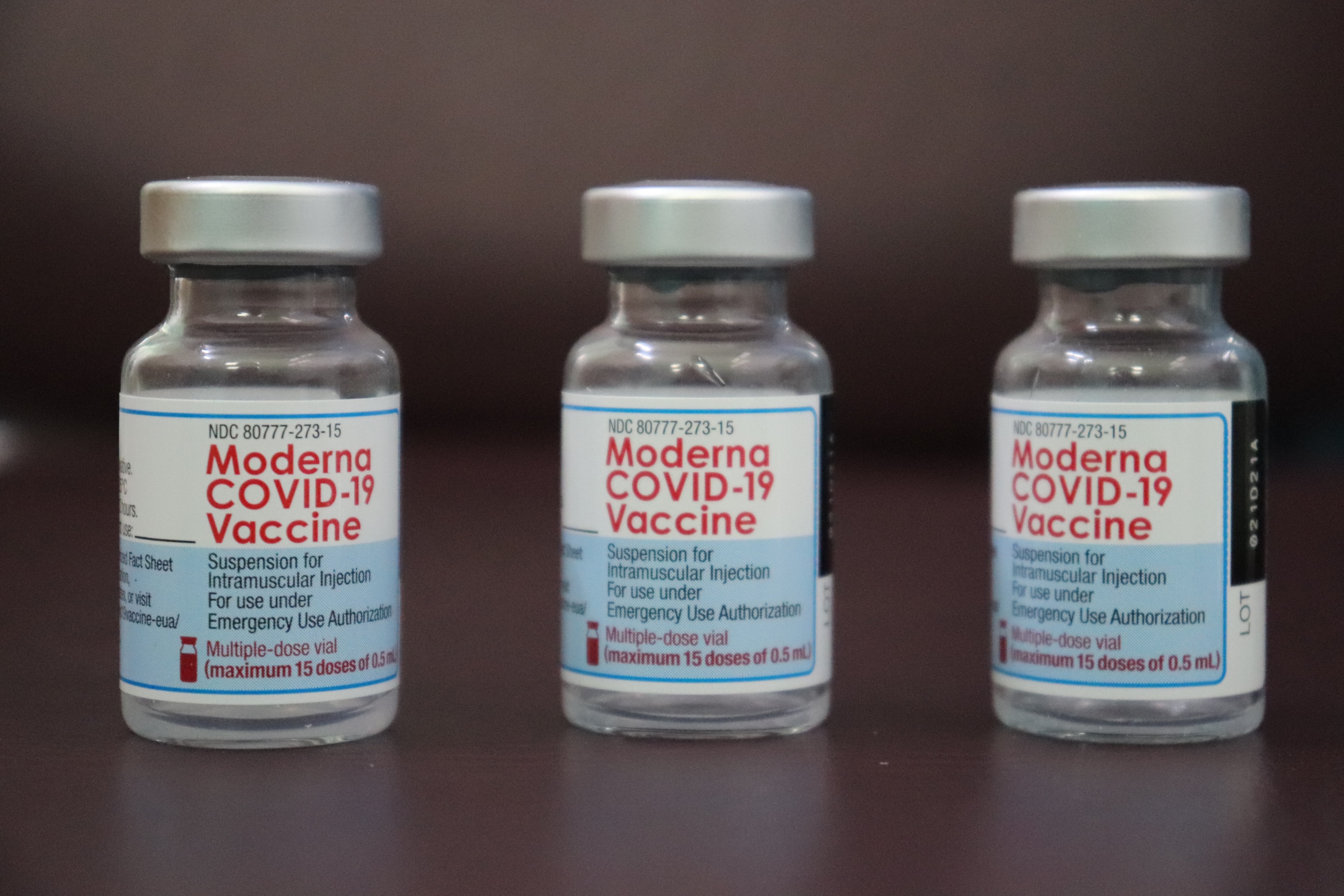

ZP Therapeutics ready to deliver the first shipment of COVID-19 vaccine Moderna to increase vaccine access in Thailand

ZP Therapeutics is ready to deliver the first shipment of 560,000 doses of COVID-19 Vaccine Moderna to the Government Pharmaceutical Organisation (GPO) for distribution to the Private Hospital Association in an effort to increase access to alternative vaccines for the people of Thailand.

10 November 2021

Zuellig Pharma and GW Pharmaceuticals sign a partnership agreement in Taiwan

Zuellig Pharma announced a new partnership with GW Pharmaceuticals (GW) to support access to cannabis-based medicines in Taiwan. GW, part of Jazz Pharmaceuticals plc, is a world leader in discovering, developing, and delivering regulatory approved cannabis-based medicines.

04 November 2021

Updates on the first shipment of COVID-19 vaccine Moderna to Thailand

ZP Therapeutics, a division of Zuellig Pharma and the official partner of Moderna in Thailand, confirms that the first shipment of 560,000 doses of COVID-19 Vaccine Moderna will arrive in Thailand within 5 November 2021, based on the latest schedule provided by Moderna.

29 October 2021

Department of disease control appoints Zuellig Pharma to handle 20 million doses Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccines in Thailand

Zuellig Pharma has been appointed by the Department of Disease Control to handle and distribute another 20 million doses of the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccines in Thailand.

08 October 2021

Making good mental health a reality

Technology like smartphones, laptops and smartwatches have blurred the lines between work and personal time even before the COVID-19 pandemic hit us almost two years ago.

05 October 2021

Zuellig Pharma receives EcoVadis Platinum Sustainability rating for the year 2021

The award is the highest accolade to be awarded to a company for its sustainability efforts and positions Zuellig Pharma in the top 1% of all assessed companies worldwide.

04 October 2021

Chulabhorn Royal Academy signs agreement with Zuellig Pharma to purchase eight million doses of COVID-19 vaccine Moderna

The Chulabhorn Royal Academy (CRA) announced an official agreement with ZP Therapeutics, a division of Zuellig Pharma on the supply and distribution of eight million doses of the COVID-19 Vaccine Moderna in Thailand.

24 September 2021

Thailand's food and drug administration expands authorisation of COVID -19 vaccine Moderna for use in adolescents 12 to 17 years old

ZP Therapeutics, a division of Zuellig Pharma today announced that Thailand Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has expanded the authorisation of the COVID-19 Vaccine Moderna for use in adolescents aged 12 to 17 years old.

23 September 2021

Zuellig Pharma wins four awards at the Asia corporate excellence & sustainability awards 2021

Zuellig Pharma, a leading healthcare services provider in Asia, has been presented with four leadership and sustainability awards, in both individual and enterprise categories, at the recent Asia Corporate Excellence and Sustainability (ACES) Awards. Organised by MORS Group, the annual ACES Awards is a prestigious accolade that recognises inspiring leaders, sustainability advocates as well as businesses' contributions to their communities and the world.

03 September 2021

Zuellig Pharma Thailand collaborates with the department of disease control (ddc) to provide nationwide distribution services of 1.5million doses of pfizer-biontech COVID -19 mrna vaccines

Zuellig Pharma is committed to leveraging our experience, expertise and our best in class cold chain solutions for distribution of vaccines, pharmaceutical and medical products to provide access to COVID-19 vaccines to the people in Thailand.

30 July 2021

Zuellig Pharma Thailand supports Chulalongkorn University to develop southeast asia's first COVID -19 mrna vaccine

Zuellig Pharma is working with Chulalongkorn University to develop ChulaCov19, Southeast Asia's first COVID-19 mRNA vaccine. As part of the ChulaCov19 mRNA vaccine programme, Zuellig Pharma managed the clinical trials, which included storing and distributing the vaccines to clinical sites.

29 July 2021

Government pharmaceutical organisation confirms purchase of five million doses of COVID -19 vaccine Moderna

ZP Therapeutics, a division of Zuellig Pharma, today announced an official agreement with the Government Pharmaceutical Organisation (GPO) to supply and distribute five million doses of the COVID-19 Vaccine Moderna in Thailand from the fourth quarter of 2021.

23 July 2021

Zuellig Pharma corporation welcomes arrival of COVID-19 vaccine Moderna doses in the Philippines

Zuellig Pharma Corporation was authorised by Moderna as the emergency use authorisation holder (through its commercialisation division, ZP Therapeutics) for its COVID-19 vaccine in the Philippines.

29 June 2021

Zuellig Pharma’s employee survey uncovers key insights to reduce vaccination hesitancy across Asia

Zuellig Pharma marked the week from 24 to 30 April 2021 with a series of events to engage employees on the topic of immunisation. This included a company-wide survey to understand if employees had concerns about vaccination and what these concerns stem from.

14 May 2021

Over 1,750 attendees joined Zuellig Pharma’s inaugural immunisation matters virtual summit

Held in conjunction with the WHO’s World Immunisation Week 2021, the landmark event saw experts across various fields coming together to lead exciting discussions on innovative ways to roll out vaccines in Asia

30 April 2021

Zuellig Pharma partners with Moderna to supply Moderna’s COVID -19 vaccine in Asia

Zuellig Pharma and Moderna, Inc. (Nasdaq: MRNA), a biotechnology company pioneering messenger RNA (mRNA) therapeutics and vaccines announced a new partnership with Zuellig Pharma’s division, ZP Therapeutics, to supply the COVID-19 Vaccine Moderna in Southeast Asia, Hong Kong, Macau and Taiwan.

28 April 2021

Zuellig Pharma clinches Ecovadis gold medal 2021 for sustainability

Zuellig Pharma, a leading healthcare services provider in Asia has been awarded the Gold Medal 2021 from sustainability ratings specialist EcoVadis.

15 April 2021

Zuellig Pharma scoops two wins at Asia-Pacific bioprocessing excellence awards 2021

Zuellig Pharma today announced that it has scooped two titles at the Asia-Pacific Bioprocessing Excellence Awards 2021. The company clinched awards for ‘Best Warehousing & Distribution’ and ‘Best Last Mile Implementation’ for a second year running.

18 March 2021

Assurance of supply chain integrity for the COVID-19 vaccine

The COVID-19 pandemic defence has entered a new phase since the start of 2021 with vaccine supplies slowly beginning to arrive in countries across the globe, as part of the internationally funded COVAX programme or through direct purchases by country governments from manufacturers.

18 March 2021

Zuellig Pharma launches ezvax, a vaccine management solution for safe vaccine distribution and administration

Zuellig Pharma today announced the launch of eZVax, a vaccine management solution that enables governments and private clients to manage all aspects of vaccine distribution and administration.

11 March 2021

How we champion supplier sustainability at Zuellig Pharma

The United Nations marked a milestone 75th anniversary last year, with a call to focus on global cooperation in building the future we want. I believe the world has made some headway with shaping this future, particularly with the launch of the Sustainable Development Goals in 2016.

20 January 2021

Zuellig Pharma achieves HR Asia’s Singapore’s best companies to work for in Asia award

In a year marked by a pandemic and continued global uncertainty, 32 companies across Singapore have been named among HR Asia’s Best Companies to Work for in Asia.

28 December 2020

Ensuring safe vaccines with eztracker

To help governments, pharmaceutical companies and healthcare providers combat the trade in fake medicines, Zuellig Pharma launched eZTracker in the region earlier this year.

09 December 2020

Zuellig Pharma collaborates with HSBC to transform collections and payments process with omni collect online solution

The solution delivers Zuellig Pharma Malaysia a bespoke end-to-end product that has streamlined their collections and payments process.

25 November 2020

Zuellig Pharma expands cold storage warehouse capacity across key markets in Asia in preparation for COVID -19 vaccine

Zuellig Pharma announced that it will significantly expand its cold storage warehouse capacity in key regional markets over the next 12 months.

19 November 2020

Face-to-face doctor consultations decrease in the philippines during pandemic, new survey reveals

Filipino doctors are conducting much fewer consultations since the COVID-19 health crisis in March this year, according to a recent survey conducted by a team of researchers from Zuellig Pharma.

10 October 2020

Zuellig Pharma begins distribution of Korea’s first COVID-19 treatment

Zuellig Pharma has signed a partnership agreement with Celltrion, a Korean leading biopharmaceutical group to distribute Regkirona (Regdanvimab) for COVID-19 patients in Korea.

02 October 2020

Placing safety at the heart of corporate culture

COVID-19 has underscored the critical role that safety plays in businesses. As Asia's leading healthcare services provider, over 350,000 hospitals, clinics and medical centres rely on Zuellig Pharma to deliver healthcare products.

28 September 2020

Zuellig pharma launches virtual care application

Zuellig Pharma has launched eZConsult, a virtual care mobile app to address the growing need for teleconsultation amidst lockdowns and restricted movement during the global COVID-19 pandemic.

06 August 2020

Celebrating international women’s day: part 2

This International Women’s Day, we interview three outstanding female colleagues from our Commercial Solutions team.

03 August 2020

Standing #zpunited in extraordinary times

Zuellig Pharma in response to the impact on the healthcare landscape, have witnessed their teams across all 13 markets and business units come together in exceptional ways to make healthcare accessible to the communities they serve.

07 July 2020

Zuellig Pharma appoints John Graham as new CEO

Zuellig Pharma announces the appointment of John Graham as its new CEO. John will run the US$13 billion business and lead the team across our 13 markets in Asia.

01 July 2020

How supply chains will evolve in the wake of COVID-19

The COVID-19 has had far-reaching effects on global supply chains. Supply chains all over the world have been put to the test as countries and businesses battle to effectively manage disruptions caused by the pandemic.

26 June 2020

Zuellig Pharma partners with Luye Pharma to distribute and market Seroquel® and Seroquel XR® in Hong Kong

Zuellig Pharma enters a partnership agreement with Luye Pharma Group, an international pharmaceutical company dedicated to the R&D, manufacturing and sale of innovative medications.

01 June 2020

Celebrating international women’s day: part 1

This International Women’s Day, we interview three outstanding female colleagues from our Distribution & Client Services team. Hear from Natalie Guo, Ngo Hong Mai and Imelda Leslie V. Rillon as they share about their role models and advice for women in healthcare.

03 May 2020

Zuellig Pharma Thailand supports ministry of public health in battling pandemic through provision of delivery and distribution services for COVID-19 treatment medication at no cost

The COVID-19 outbreak has seen more than 1,800 infected patients in nearly all provinces within Thailand. This aims to support the country in its fight against the virus.

02 April 2020

Zuellig Pharma joins Poseidon network as main distribution partner in Asia Pacific

Zuellig Pharma announced that it has joined the Poseidon integrated pharmaceutical ocean freight network as the principal distribution partner in Asia Pacific. It is also one of the latest members to be part of this network of more than 30 pharma companies and logistics providers which comprise the global Poseidon cold-chain reform project

12 March 2020

Celebrating international women’s day: part 3

This International Women’s Day, we interview three outstanding female colleagues from our CareConnect team. Hear from Lily Lan, Karen Goh and Sirena Loh as they share about what motivates them, their female role models and words of wisdom for women in the healthcare industry.

10 March 2020

Zuellig Pharma acquires Alliance Pharma (Cambodge) in Cambodia to strengthen Indochina presence

Zuellig Pharma, a leading healthcare services provider in Asia, has announced that it has acquired a controlling stake in Alliance Pharma (Cambodge), a leading healthcare distributor of Cambodia.

03 March 2020

Zuellig Pharma launches blockchain-based eztracker in Thailand to help consumers verify authorised aesthetics products in seconds

Zuellig Pharma has announced the launch of eZTracker in Thailand and partnered with global pharmaceutical company, Galderma (Thailand) Ltd to help consumers identify unauthorized aesthetics products

15 February 2020

APL inaugurates largest national distribution centre in Indonesia

As part of their commitment to increase healthcare access in Indonesia, PT Anugerah Pharmindo Lestari (APL) officially introduced its new state-of-the-art National Distribution Centre (NDC), located in West Java, Indonesia, on 3 February 2020.

14 February 2020

Zuellig pharma awarded ecovadis silver medal 2020 for sustainability

Leading healthcare services provider Zuellig Pharma has received a Silver medal from sustainability rating specialist EcoVadis for its commitment to driving sustainability within its business.

22 January 2020

Zuellig Pharma provides the eZCooler solution and training to improve vaccination outcomes in Vietnam

As part of the partnership with the National Institute for Control of Vaccines and Biologicals (NICVB) and the National Institute of Hygiene and Epidemiology (NIHE) to improve access to vaccination in Vietnam, Zuellig Pharma Vietnam organised an event to handover US$600,000 worth of the eZCooler solution on 20 December 2019.

21 January 2020

Philippine Academy of Family Physicians collaborates with eZConsult for family and community engagement through Telehealth service (Facets) programme

The Philippine Academy of Family Physicians (PAFP) will collaborate with telemedicine app eZConsult as the digital platform for its remote consultation initiative dubbed Family and Community Engagement through Telehealth Service (FACETS)

15 January 2020

Zuellig Pharma enters into strategic partnership with Eli Lilly and company in Malaysia and Thailand

Zuellig Pharma, a leading healthcare service provider in Asia, is pleased to announce two new strategic partnerships with Eli Lilly and Company (Lilly) to market, sell and distribute the healthcare manufacturer's existing and new products in Malaysia and Thailand.

22 October 2019

Mölnlycke and Zuellig Pharma strengthen partnership for advanced wound care solutions in South-East Asia

<span style="background-color: #ffffff; color: #000000;">The commercialisation of Granulox and Granudacyn in South-East Asia was previously managed by SastoMed’s exclusive strategic partner, Zuellig Pharma, one of Asia’s largest healthcare services provider.</span>

05 July 2019

Zuellig Pharma acquires healthtech start up Klinify

Zuellig Pharma has acquired Singapore-based Healthtech start-up Klinify, to support the development of technology that empowers doctors to modernise their practices and simplify workflows. Klinify is a cloud-based digital medical assistant used by over 800 doctors in Malaysia to manage their clinics more efficiently.

30 May 2019

Zuellig Pharma, NICVB and Nihe announce project to expand access to vaccines in Vietnam through the use of innovative ezcooler solution

Under the agreement, Zuellig Pharma will contribute hundreds of the innovative eZCooler solution, a temperature-controlled packaging technology to maintain product quality during transportation.

18 April 2019

Why healthcare needs to break down the great wall of data

Many organisations struggle with consolidating and translating the wealth of data they have into actionable insights because the data sits in segregated silos. These silos stem from the need to comply with strict data privacy policies and laws, resulting in various clinical, financial and operational data being housed separately.

11 April 2019

Our People

Celebrating International Women's Day with Byun Soo Yoon, Head of Logistics Zuellig Pharma Korea

27 March 2019

Our People

Celebrating International Women's Day with Pucknalin Bulakul, Chief Operating Officer Zuellig Pharma Thailand

27 March 2019

Our People

Celebrating International Women's Day with Tan Yan Ann, Chief Executive Zuellig Pharma Singapore

19 March 2019

Our People

Celebrating International Women's Day with our VP Procurement Victoria Folbigg

12 March 2019

.jpg?h=210&iar=0&w=617)

.jpeg?h=165&iar=0&w=280)

.jpg?h=408&iar=0&w=1200)

.jpg?h=681&iar=0&w=2000)

.jpg?h=408&iar=0&w=1200)

.jpg?h=409&iar=0&w=1200)

.jpg?h=165&iar=0&w=280)